Introduction

‘There are tides in the body’. This quote by Virginia Woolf (2012, p. 81) greets the visitors at the recent Art Exchange exhibition Live Streams . The exhibition was held between the 28th of April and 27th of May in 2021 and it was curated by Lisa Blackmore 1 , Diego Chocano 2 and Emilio Chapela 3 , all part of entre —ríos, a collective of artists and researchers who in their projects attempt to touch upon environmental themes with the help of the arts.

The aforementioned introductory metaphor of Woolf acts as a guide throughout the whole show. The use of symbolic terms is, according to Jung (1964, p. 21), a way for us to ‘represent concepts that we cannot define or fully comprehend’. Yet, entre —ríos are quick to regard Woolf’s quote as literal, equating both the matter and the processes of rivers to the human body. The natural opposition that we come to expect between metaphor and fact is thus blurred, opening doors to knowledge that invites the seemingly contrasting elements to converse.

It is this refusal to think in binary terms that defines the Live Streams exhibition, where human/nature, culture/nature and online/offline are no longer separate entities existing within their predetermined boundaries. These opposites came together in the exhibition which was opened to both online and ‘real-life’ audiences. A dual existence that embraces the strict rules forced upon us by the COVID-19 pandemic, compelling us to look at the supposedly separate sphere of the World Wide Web as having the ability to impact the so-called ‘real’ world and therefore as a part of it. Aside from revealing the epistemological limitations that we put on ourselves, Woolf’s quote is used as an invitation to a journey that is as much personal, as it is collective. The idea that ‘there are tides in the body’ makes us visualize the complex, intersecting channels of flowing water within our own interiors. It is almost as if one has to say ‘there are tides in my body’ before broadening one’s gaze and applying this statement to others.

Analysis of the Artworks

It is precisely this fusion of collective and personal that underlines the works of contemporary Peruvian artist Genietta Varsi, who in her works deals with the mutually transformative relationship that bodies have with nature. Before I had the chance to fully engage with the objects presented in the exhibition, I attended the online-held exhibition launch event organized by the show’s curators, where they introduced the backstory of the show and the entre —ríos collective behind it. The event also featured a breathing workshop led by Varsi, where the participants were invited to follow the artist’s commands. Spatially separated from each other yet brought together to the same virtual space with the help of Zoom, we had to sit or stand, and imitate the shape of a heart by holding our hands next to our chest and then lay them down on our thighs in a position more typical to meditative exercises. We took deep breaths and then held them in. We also did the opposite by letting all the air out of our lungs, feeling tingling sensations all over our bodies as the time passed. It is these breathing exercises that allowed us to feel a deeper connection with the flowing waters: how our lack of oxygen and the increasingly excessive amount of carbon dioxide mimics the nature of polluted rivers. This imitation of drowning replaced any previous thoughts and sources of stress (the Damocles sword of my impending exams was, even if for just a minute, nowhere to be seen) and left us in the all-consuming and ever-expanding darkness.

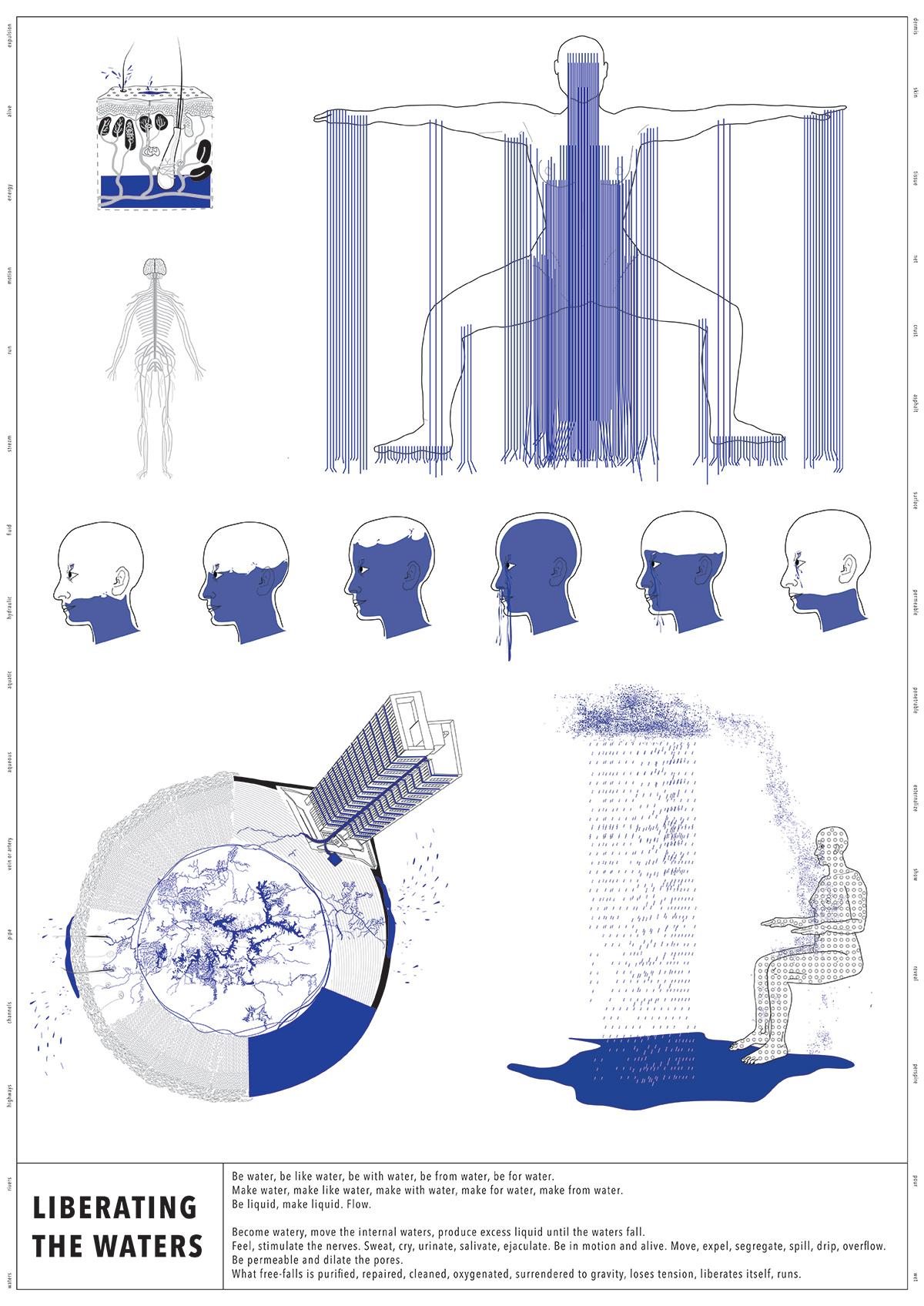

I am aware of the overly dramatic word choice in describing the peculiarities of the experience, yet I can assure the reader that the fear brought on by these sensations was utterly real. Looking retrospectively, these types of exercises allowed for a different temporal perception that is antithetical to the usual sixth gear of the social media age. The inability to think of anything but that vital breath of fresh air (which I could equate to feeling parched on a hot summer’s day, knowing full well that only a cold glass of water could satisfy the enormous thirst) made the short and long hands of the clock switch positions. As Varsi’s voice finally allowed us to continue our natural breathing cycle, and as various thoughts finally rejoiced in having the space to play again, I began to wonder: can we truly call these sorts of practices ‘art’, or does it expand our notions of this already hard-to-pinpoint term? In the posters accompanying the videos she produced for the exhibition, Varsi seems to playfully engage with this notion by producing scientific depictions of the human body and its processes and then subsequently undermining them. For example, in the digital print titled Liberating the Waters (Varsi, 2021) (Figure 1), an accurate depiction of a skin cell and a model of the human nervous system are visible on the top left corner. One would expect to find these images in their biology schoolbook, but they are offset by the unfamiliar image of the spread-out human figure. Despite the bearing striking resemblance of the figure to the symmetrical Vitruvian Man - an image that itself fuses the artistic with the scientific due to Leonardo da Vinci’s inquisitiveness into both spheres - the blue vertical lines falling to the ground showcase the loss of water through myriad of channels within the human body. The same can be said about the cycle of crying depicted through the presence of six human heads, with the water steadily filling up the head to a point where it has nowhere to go but through the passages of its lacrimal glands - an illustration that is more metaphorical than science-related. Therefore, the scientific undertones are convoluted by the artist’s panache, denying the didactic insight one would expect to gain from similar material.

Figure 1:Liberating the Waters (Varsi, 2021)

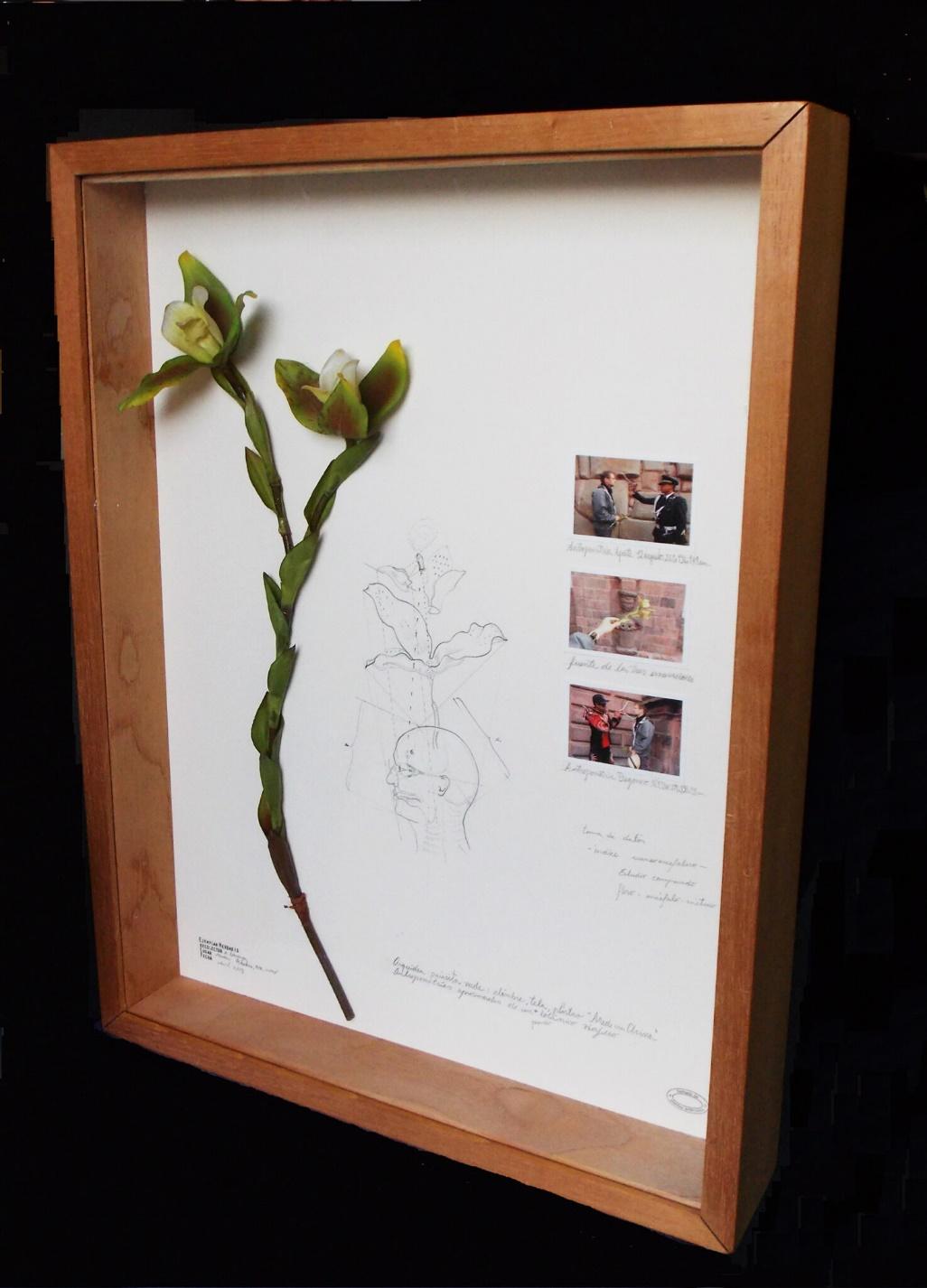

Figure 2: Expedición Machu Picchu: Orquídea parásita verde (Baraya 2013)

Alberto Baraya, whose work Expedición Machu Picchu: Orquídea parásita verde (2013) is depicted in Figure 2, is known for his simulations of anthropological expeditions. In this artwork, he once again steps into the shoes of a colonial-era explorer. The artwork belongs to the Essex Collection of Art from Latin America, an integral partner of the exhibition whose works broadened the conversation kindled by entre —ríos. Expedición Machu Picchu is an example of the fusion between art and science that permeates the exhibition and exchanges Varsi’s playfulness for a piercing critique into the supposed objectivity of scientific practices. The multimedia artwork features a found object in the form of a plastic flower. A drawing with scientific measurements, and pictures showing the performative aspect of the work, with notes scribbled across the piece accompany it. The artwork resembles a plucked page from an authentic diary of a scientifically curious colonial traveller. Baraya, as seen in the photographs on the right side of the work, invites other people to measure his head using a thickness compass. A famous practice in the French-developed criminal identification system (Sekula, 1986, p. 11) as well as in the pseudo-scientific phrenological studies made by the colonizers to fathom and more importantly to assert the difference of indigenous communities (Bank, 1996, p. 389). What is interesting, is that although Baraya is presented by the artwork description as the colonized traveller, he is not the one who conducts the measurements; rather, he gives this task to the locals, thus subverting the actual custom. The notion of power is therefore brought into the fore, with the artist subjecting himself to the role of a passive inhabitant, a mere object for the more powerful. The pictures also depict Baraya holding a flower during these measurements of the skull; the same one that then towers above the rest of the objects within the artwork. A herbarium of sorts that mimics the way real people were treated as if they were samples of plants. A pre-set goal to treat different people as the ‘other’ and use science (or pseudo-science as phrenology is now rightfully regarded) to systemize them, is a way in which knowledge is subverted into a tool of suppression, giving power to one group, yet marginalizing the other.

Moving my gaze from the entre —ríos webpage to Art Exchange, the Essex University’s gallery space (albeit, still remaining within the confines of my computer screen, as I am simply transitioning to the Art Exchange’s website to get a sense of the physical part of the exhibition), I am immediately fixated on Emilio Chapela’s Salto del Tequendama (2021). Granted, I doubt I am the only one, as its position is roughly in the middle of the gallery, with its towering size and mode of presentation making it immediately noticeable. The artist continues his practice of finding multidisciplinary connections by focusing on natural phenomena, which in this case is a waterfall. A linen fragment is hung from the ceiling; its length forces it to nest on the floor; its end tightly wrapped in a scroll-like manner, as if the work is not fully complete and the story it aims to tell continues to be written. By comparing Chapela’s work to a scroll, I begin to look at it as if it was a text, a non-traditional one of course, that aims to convey a message to its viewer. The idiosyncratic, wave-like shapes of the acrylic paint invoke a certain texture, an invitation to a sensory experience that fuses vision and touch. I wonder if it is like braille writing: will scurrying my finger across one of the layer-like lines make me receive the message of the artwork? As transgressive gallery practices like touching the artwork begin to enter my mind’s periphery, I attempt to subside the bubbling academic within me and instead just look. The work is simply beautiful: a variation of colours stream down the linen, alternating between hues too numerous to mention. I find myself particularly enjoying the middle section, where orange meets yellow, with the accompanying azure blue highlighting this intersection. I begin to search for a pattern, for a reason as to why the colours are positioned in such a way. This is a sign that my rational thinking has arisen from its deep slumber of two minutes. In order to continue looking without its interference, I accommodate reason by throwing it a bone of ‘I do not know’ that it then chases out of the chambers of my mind.

With no one to disturb me, I return to the aesthetic pleasures. I realize how wonderfully abstract this work is, how, by enveloping you in its formal qualities it almost overshadows the deeper contextual layer hiding behind its shapes and colours. Seeing Cy Twombly’s Untitled (Bacchus) (2008) was a similar experience, as I tried my hardest not to engage with it critically out of fear of ruining this rarely-occurring opportunity, allowing for a spiritual experience to consume me, passing the reins over to feeling as opposed to the usual suspect of control – the aforementioned reason. Once again, this moment of awe that I am describing does not last for very long and the academic curiosity forces me to shift my attention (this time for good) towards the meaning of the artwork.

Chapela had a dream of the Salto del Tequendama (yes, merely a dream, as he has never, in fact, been there; only photographs and videos of friends introduced him to the natural splendour of the waterfall) and within that dream he dropped his camera down the many-litres-of-water-per-second pumping waterfall, finding its journey’s end at the depths of the polluted waters of Bogota River in Colombia ( entre —ríos, 2021). These pollutants turned into lines of colour and then subsequently, after the inspiration from the indigenous thinker Ailton Krenak, became parachutes. This gradual transformation of a visual within a dream to a three-dimensional object within ‘reality’ highlights how the former is part of the latter, connecting to the predominant theme of the exhibition by once again showcasing that the elements we came to think of as separate are actually entwined in a dynamic relationship. According to Chapela, the dream that inspired the artwork made him realize that for a while he was falling as well ( entre —ríos, 2021). Thus, the recontextualization of lines of colour into parachutes, whose function is to make the whole ordeal of falling a safe enterprise, is a way to take the fear out of falling and instead make us embrace it as a necessary component of life and growth that one is inevitably forced to undergo. (Think of the drowning orchestrated by Varsi, my rational mind nudges me.)

Figure 3: Salto del Tequendama (Chapela, 2021)

The audience members who are adamant on experiencing everything Live Streams has to offer, whether it is the online or the offline version, will inevitably spend most of their time engaged with the video works, as they make up most of the exhibition’s material. The Colombian visual artist Eulalia de Valdenebro, whose work attempts to peace the gap between the natural and the human, is featured in the exhibition with Cuerpopermeable (Figure 4). A video series showcase the artist becoming different elements, turning her body into a vessel of mist, lake, and wind, creating a connection between different types of bodies, fusing human and nature, highlighting the communicative capabilities of our bodies and their origins as the first contact with the world surrounding us. Communication is also at the forefront of Mexican artist Tania Candiani’s oeuvre - specifically how certain places trigger various temporal and spatial links. Songs for Magdalena and Yamuna (2013-21), are two side-by-side videos depicting two canoes, which are holding the same gramophone at their bow, one playing Blue Danube while the other responds with a grief song in Hindi. One is carried by the waves of Magdalena in Colombia, while the other is swayed by the waters of Yamuna in India. The temporal difference of eight years and a spatial distance of over 15,000 kilometres does not seem to hinder the communicative yearnings, as the songs take turns transforming the vibrations of the vinyl into amplified sound. If we were to translate this conversation into a language familiar to our ears, we would undoubtedly hear a lot of common experiences that these two polluted rivers share.

Figure 4: Cuerpopermeable (de Valdenebro, 2021)

There is a connection here to be made between Candiani’s work and that of the experience of the events in the exhibition’s public program. As everything else in the past year and a half, so did the events seek refuge within Zoom video conferences. Yet, there was something particular about these virtual events, something that made them stand out from all the lectures, classes, or meetings. First of all, similar to Candiani’s work, Varsi’s breathing workshop and Vásquez’s meditation-centred event (with fascinating gramophone-like contraptions that transform the uneven and history-steeped surfaces of stones collected at the bank of rivers into primordial sounds which the artist dubs ‘The Grandmothers’ songs’) pay a lot of attention to the body. It is quite easy and natural to feel alienated using a software like Zoom. Looking at others and ourselves as just identically sized rectangles on a black screen, each sitting in front of our computers with undescriptive backgrounds masking our current geographical location, separated from each other by a thin black outline makes us feel estranged. There is also an often-occurring tendency to forego video altogether, to use only our voices to let others know that we are listening, critically engaging, that we are, in fact here. Yet, even if the above-mentioned, despair-laden words do ring true to some experiences each of us might have had, it does not always have to be so dystopian. There is an ever-present chance to inject our bodies into virtual spaces and be amazed at the communal opportunities that they provide. For example, during Varsi’s workshop we were asked to turn on our microphones and cameras in order to have this experience of shared space in a fragmented world that is anything but. Even though my reticence denied this request, I was still able to see and hear the breathing of others. There was one instance where we were told to make various shapes with our lips and press the air out in different volumes, seeing how the sound changes accordingly. Being able to hear others being unafraid to let out the strangest of sounds quickly dissipated the awkward atmosphere and did, in fact, overcome the supposed limitations of a virtual social space.

Conclusion

There is so much more to be said about the exhibition and both its overarching themes and the various individual investigations conducted by each artwork. What my own condensed perspective and the musings that flow from it should reveal, is the meditative concentration of the exhibition that brings to the fore the vast capabilities of our bodies that go beyond the roles of vessels of the mind. The strong interdisciplinary foundation of scientific inquiry within the exhibition makes such notions something more than mere metaphysical ponderings, but, I believe, travels back in time to a more primordial relationship that encompassed bodies with other living matter. Rivers are the example that Live Streams uses, and it is indeed a way to turn the metaphorical into the real, to make the body flow and inspire hope through the healing capabilities of streaming waters. In the ever-continuing pandemic we need to know that things could get better.

References

Bank, A. (1996). ‘Of “Native Skulls” and “Noble Caucasians”: Phrenology in Colonial South Africa’. Journal of Southern African Studies , 22(3), pp. 387–403.

Baraya, A. (2013) Expedición Machu Picchu: Orquídea parásita verde . Found object: Drawing and photographs on paper. Essex Collection of Art from Latin America, Colchester.

Chapela, E. (2021) Salto del Tequendama. Acrylic paint on linen. Art Exchange.

de Valdenebro, E. (2021) Cuerpopermeable VIII: Neblina . Video still. Art Exchange.

entre —ríos. (2021) Emilio Chapela . Available at: https://entre-rios.net/emilio-chapela/ (Accessed: 19/11/2021).

Jung, C. G. (1964) Man and his Symbols . Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Sekula, A. (1986) ‘The Body and the Archive’. October , 39, pp. 3-64.

Varsi, G. (2021) Liberating the Waters . Digital print. Art Exchange.

Woolf, V. (2012) Mrs Dalloway . London: Alma Classics LTD.

© Povilas Gumbis. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence (CC BY).