Note from the editor

This paper is a critically reflective essay, so the views expressed represent the author’s personal perspective.

Introduction

Hess (1995) describes the importance of learning through one’s entire life, not as a product of experiences, but as a sequence of steps in many directions. Therefore, learning does not just depend on the end results or outcome of a project but must be something received through each step along the way. This reflective essay examines the self-critique used to challenge how my own role as an educator should be shaped within changing teaching contexts and how the lessons learned from these changes need to reflect in my own practice as I move towards self-awareness and self-improvement. This process was completed through the lens of a key transformative learning theory and after experiencing a “trigger” or disorientating event.

The essay aims to demonstrate the significance of decision-making and critical reflection on professional practice. Critical synthesis is often necessary to facilitate personal reflection on practice which requires complex decision-making. Therefore, a reasoning process enables an individual to make meaning of an experience and engage in self-improving tasks (Ash & Clayton, 2009). This reflective essay illustrates this meaning-making process and discusses its importance in my personal journey from a military instructor to a facilitator of learning within a higher education institution (HEI).

Critiquing your own habitual teaching strategies and approaches may not be easy but it comes with invaluable results that help to elicit the positive and negative behaviours that you may, sometimes unconsciously, display (Cranton, 1996). Through a comprehensive critical reflection, I was able to examine ways of bringing positive changes to my professional practice and it also gave me an opportunity to reflect on a range of issues that may influence this, including my personal life.

Reflective Learning

Numerous literary accounts of reflective learning indicate enormous intellectual interest in the intricacies of the concept and its practical implications. As healthcare providers, practitioners and medical professionals have been shown to favour this process of learning, reflective learning has emerged as a vital means of improving individual skills in these fields (White, Fook & Gardner, 2006).

Dewey's (1933) theory of reflective thought and action, Kolb’s (1984) four-stage model of experiential learning and Gibbs’ (1988) reflective cycle are three widely used models or theories of reflective learning. Dewey's theory of reflective thought and action was based on the premise that learning for people should come from participation in relevant learning experiences (Hess, 1995). Dewey’s work was significant in its importance to experiential learning or learning-by-doing theories because it explained what kind of experiences lend the most learning opportunities. Kolb’s experiential learning model, which was an extension of Dewey’s theoretical paradigm, further discussed the significance of learning as an integral product of the range of events and situations that one comes across in daily life. Gibbs’ reflective cycle acknowledges the influence of personal feelings on individual reflections of certain experiences (Dix, 2016).

All of these models have received acclaim for being a good starting point for reflective learning. In their own ways, they each attempt to encourage individuals to become aware of all distinctive stages of learning, such as describing an event, evaluation of feelings about the event, learning good or bad from the event, analysing how the situation could be used for learning and creating some kind of action plan for what is lying ahead (Kolb & Fry, 1975). However, these models are often criticised for only facilitating superficial learning, with little or no references to critical thinking and critical learning practice.

Transformative Learning Theory

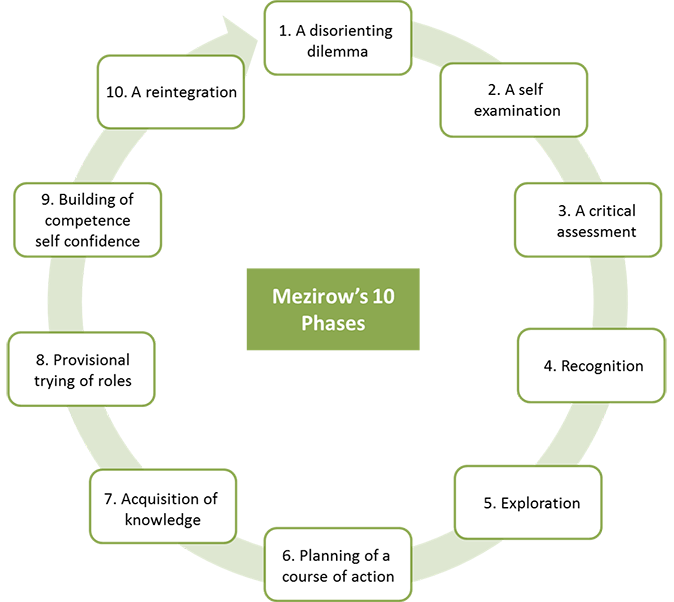

Mezirow (1991) developed transformative learning theory (TLT) to describe how people use critical self-reflection in considering their experiences and seeing the world through them. Mezirow emphasised an interpretation of people’s worldviews that leads them towards a different view of the world. He outlined a 10-phase process that contributed to transformative learning (see Figure 1):

Figure 1: Mezirow’s 10 Phases of Transformative Learning (Kabakci & Şahin İzmirli, 2015)

Mezirow described how a ‘disorienting dilemma’ occurs when an individual experiences an event that does not fit in their previously held worldview (Ash & Clayton, 2009; Dix, 2016). Resultantly, such experiences challenge the individual to reconsider their values and beliefs so that the new experience matches the rest of their worldview. Thus, critics acknowledge a shift in Mezirow’s interest from philosophies of consciousness towards philosophies of communication (Brookfield, 2009; Redmond, 2017). One of the disadvantages of TLT was claimed to be the emphasis on ideal conditions of self-directed learning, which is challenging for most professionals. Additionally, others have claimed that the theory was devoid of a socio-political critique and a contextual understanding of ideology was missing (Miettinen, 2000).

According to its original theorist, TLT is a process by which prior understanding or interpretation of an individual is used to construe new meaning or new understanding about an experience with the intention of guiding future courses of action based on the new-found understanding. This is essentially, an idealised model of adult learning which tends to pinpoint differences between learners as repositories of knowledge or active learners who are involved in a critical reflection and deeply engage with the context to achieve a deeper perspective that guides their future action (Brookfield, 2009; Holt & Kysilk, 2005; Leon, Pinkert & Taylor, 2017). Previously held beliefs, according to Mezirow, become stronger with time, only to turn into unconscious frames of reference. The entire process of transformative learning involves paradigm shifts in the discovery of new knowledge in a way that causes the learner to critically reflect on their own thoughts and interpret experiences in the new light only to find their past knowledge has been changed or transformed into new.

It is very difficult for an individual to alter these beliefs or challenge such assumptions (White, Fook & Gardner, 2006). These frames of reference are so strong that they cannot change the individual’s view of the world in its basic instance. However, Mezirow argued that in order to challenge one’s previous beliefs, values and assumptions, a disorienting dilemma (trigger event) is often needed (Mezirow, 1991). A disorienting dilemma or trigger event occurs during the process of perspective transformation whereby people come across experiences that do not match with their experiences unless they alter their worldviews based on the knowledge gained from the triggering experience or event. A critical reflection on assumptions is often the best way through which subjective reframing of the previous frame of reference takes place as soon as an individual is triggered by a disorientating dilemma. Following Habermas’ (1971) domains of learning (namely practical, technical and emancipatory), Mezirow built his idea of perspective transformation on these meaning structures called ‘meaning perspectives’ and ‘meaning schemes’. While meaning perspectives are composed of psycho-cultural assumptions that define our expectations, meaning scheme is generally the constellation of judgements, beliefs and concepts that shapes our interpretations in a specific form or direction.

Meaning Making

Military Instruction

My previously held beliefs were no different to what Mezirow based his epistemic critical reflection on assumptions. I had always experienced that teaching and learning styles in a military environment were unidirectional and purely instructional; where the teacher will teach and the students will learn without having the power to challenge or question what is being taught. This however can lead purely to rote memorization where the students’ critical thinking and problem-solving abilities are completely inhibited. This method can be beneficial where safety critical instruction takes place such as firearms or weapons training or emergency medical care. Subjects such as these require knowledge and skills to be taught so that students can rely upon them under duress and in extreme environments. There is often no time for critical thinking on the battlefield and successful implementation of these skills is commonly derived from repeated practice and muscle memory in simulated environments. Indeed, the need to simulate real-life danger in order to fully prepare military learners for battlefield scenarios meant that high levels of risk were tolerated, even in the simulated learning environment and therefore strict rules and instruction had to be enforced for everyone’s safety. Being an authoritarian military instructor, I had the opportunity to acceptably punish my students (in case of breaking the rules) a lot more than in other learning environments. This meant that I could create an environment where students were disciplined, had a clear understanding of their responsibilities in the classroom, asked fewer questions and accepted everything as I defined it.

After many years teaching in this type of military environment, I felt comfortable in this setting, with little room for student creativity, innovation or emotions. One of my previously held beliefs about military teaching institutions was that they could not afford to pay any attention towards students with emotional problems or varied learning styles and would solely be limited to demanding practical training or knowledge learned verbatim. I also thought that teachers in military education institutions should be seen as masters of the subject matter and the confidence gained from achieving this position would allow excellent interpersonal skills. Without these traits, I believed teachers involved in military education could not function effectively.

A critical reflection of assumptions is often not easy as people prefer to avoid thoughts that disturb or challenge their previously held perspectives. Emotionally, our actions are emotionally centred on what we feel is easy or convenient to think. With these previously held beliefs in mind, I would like to mention here the premise of my perspective transformation which comprised of my meaning perspective and meaning schemes:

Identified Meaning perspective:

Teaching is a noble calling, in which I will be able to maximise the knowledge and information of my students in order to bring out the best in them. I also assumed that teaching requires a didactic approach where the students depend only on the teachers for instruction.

Identified Meaning schemes:

• Through teaching, I am able to impart specialist knowledge because I have it

• Teaching means teaching students who will be willing to learn from me

• Lack of negative feedback from learners indicates I am a successful teacher

• I can exercise power over students and can force them into listening to my instructions

Trigger Event (Disorientating Dilemma)

Business as Usual

As previously mentioned, transformative learning theory crucially hinges on a “trigger” event or disorientating dilemma. For me, this happened whilst I was teaching employability skills at a HEI, shortly after leaving the military. My previously held beliefs were extremely at play when I started this role, hoping to manage a class full of students who knew they were there to learn from their teacher and gain from my knowledge. To me, I was teaching very successfully to a class of students who were meant to be introverted, keep their emotions out of the classroom, and were not allowed to challenge my unidirectional style of direct teaching.

Being experienced in the field, I was also proud of my authoritarian style of teaching the pupils, which I thought will be very well-received by them. I expected from my students what could be called absolute obedience to my commands, which in my view was helpful in preparing them for the career challenges that lay ahead of them. In my traditional style, I encouraged my students to resort to conventional thinking methods and not question or deviate from the instructions given to them. I determined some solid rules for the entire class to abide by, through which it became convenient for me to measure or gauge students’ performances, regardless of their personality traits.

Student Feedback

I had not anticipated any disorienting dilemmas in this specific teaching session until the time we were required to ask the students for feedback about teacher efficacy and teaching capabilities. Like always, I had assumed that students would be given a task and they would complete it promptly without questions asked. This was the very first time I had been required to proactively request my learners to give feedback, by filling out a questionnaire (as anonymous respondents) and so, I was excited to hear all positive, good news about my teaching style. Much to my disbelief, I received overwhelmingly negative feedback. The majority of the students did not appreciate my teaching style at all, complaining that they felt uninterested and disengaged in my class. This was surely a disorienting dilemma that I was experiencing, and it began to make me challenge my own inner assumptions about the efficacy of authoritarian teaching methods. Despite all the qualifications, experience, knowledge, and teaching abilities that I possessed, it was clear from the feedback that I was not successful in keeping the class engaged in what I taught them and that the majority of the conceptual knowledge I provided them was left unabsorbed. It had proven all my previously held beliefs wrong and had shown me how miserably frustrated my students were in my class.

Having excessive rules in the classroom and clear-cut boundaries did not help either. The students felt that the class was extremely boring, non-empathetic to students’ problems and emotions and left little opportunities for them to think and do creatively. Most of my students reported similar attitudes and feelings towards my teaching style and expressed their distress and inconvenience in terms of being able to digest what was taught and applying it in real-world issues or experiences. They felt there was hardly any need for them to sit in the class, as they found themselves very distracted, could not develop any communication or cooperation with other members of the same class and felt completely lost amidst a glut of theories and other information about the subject.

Evaluating the Situation

I reviewed my performance in the classroom, while continuously challenging and contesting previously held beliefs and assumptions. To me, it appeared that my authoritarian personality and protective nature were also my biggest enemy that had disrupted my professional life, influencing what I do and completely inhibiting the “goodness” and positivity in me. This triggered a sense of reviewing my practices and changing them to avoid any major setbacks again. I found out that apart from a handful of students in a class of thirty, everyone else felt disengaged and uninterested. They were only coming to the lectures because it was required of them to be able to pass the module and there appeared to be little engagement existing in the class to encourage passionate learning from them. This feedback led me to feelings of humiliation and, to a degree, shame. I was genuinely embarrassed at what I had been forcing the students to put up with. It seemed I had completely been unsuccessful in nurturing the young minds and I had failed to adjust to the new teaching or learning environment. This made me question my personal beliefs around the role, identity and styles of teaching or learning very strongly. I was only left with a few possible courses of action to help overcome the situation:

1. To ignore the feedback and continue teaching in my conventional style regardless

2. To acknowledge the feedback and ignore the action needed on it

3. To acknowledge the feedback and bring positive change in my teaching style based on it

I took my time to evaluate each option and soon realised that options 1 and 2 would not work. These were both counter-productive to student success and could lead to extreme burnout or failure for the students. This would be detrimental to what I set out to do- to impart knowledge and contribute to greater student learning outcomes. Hence, option 3 was the only viable option I was left with. It was high time I adopted an alternative teaching style or strategy to encourage learning among my students and allow them to grow and change. It urgently required me to implement appropriate teaching strategies to create a positive learning environment in the classroom.

During this time, it dawned on me that instructional teaching is only successful if it is combined with a sense of flexibility towards student output and I came to the very sobering realisation that these professional traits could also be affecting relationships in my personal life. I now saw that similar issues in my personal and professional working relationships after leaving the military could clearly be linked to me not adjusting well to my new role or identity within civilian life.

Root Cause Analysis

Role Identity

Identity plays a pivotal role in shaping self-concept as the various components of our personal or professional identity help to define how we see ourselves and, importantly, how we wish others to view us (Cranton, 1996). An identity provides a meaning-making tool by virtue of which personal orientation or orientation about oneself is obtained. Different perceptions of our identities tell us what the world thinks about us, which in turn, helps establish self-concept i.e., what comes to mind when we think about ourselves (Kolb and Fry, 1975). Identities are influenced by others’ perceptions of us, such as feelings of respect or disrespect, trust or mistrust, and honesty or dishonesty, which help shape our status in society. Role identity is important for all roles we fulfil in life and is arguably exaggerated in professional roles such as the military, where strong associations with status, rank and power exist.

Acknowledgement of the influence of role identity is integral to professional development and the means by which I came across the disorienting dilemma not only encouraged my understanding from newer perspectives, but it also showed me how my teaching style was affecting my personal life. I had adopted, without really knowing it, an authoritarian style of teaching students within the military. My perception of a teacher based on the existing schemes of meaning was not only reinforcing my idea of self but also of my position and stature within the educational institution. This is not to say that self-concept is a product of only one component; it is a by-product of different, smaller components or aspects such as my role in the family, my role in the social circles, my professional role and my role as per the perceptions of my family and friends. All these components come together to define who I am. Hence, a deconstruction of self-concept was not the result of the analysis of any one component of my personality; rather, it was a product of different smaller yet crucial components that come together to shape who I am.

Before receiving this feedback, many of these external components, including peers and the senior management of the educational institution, reinforced my image of self and therefore strengthened my belief in my own identity and teaching style. As an authoritarian personality, I was indirectly reassuring myself that my perception of the self is actually the most righteous one and that I was actually benefitting from this personality trait. Through an exercise of control, power and coercion, I assumed that there was a certain efficacy in my role that makes use of these traits and that these can be best utilised in the professional I was. However, by setting firm boundaries between myself and the students, I had actually mitigated any form of engagement and this had created an insurmountable distance between myself and my students. Before such realisation, I did not recognize this as an integral part of my identity and therefore could not understand how my actions could lead to a passive experience for the students.

The Higher Education Environment

As previously discussed, the environment in which I was now teaching had changed dramatically. No longer working within a more authoritarian, military setting, my teaching was now taking place within a higher education (HE) institution. Education within HE and universities is designed to specifically foster creativity, discussion, critical analysis and independent thought. This environment enables students to explore new ideas and solve problems in a challenging but supportive way (Chickering and Gamson, 1987). In many ways, this environment is the exact opposite of the military environment, where obedience, repetition and discipline are the fundamental building blocks of learning. Learning in military environments can allow large amounts of safety-critical information and skills to be learned in a cost and time-efficient manner. However, it often does not allow for the critical thinking and problem-solving required for deeper and more sophisticated levels of learning. I realised that without adapting my teaching to these different environments, I was unable to offer students the transformative learning experiences they required and deserved.

Facilitating Education

One of the most profound lessons I experienced after an analysis of the disorienting dilemma was a realisation of a teacher’s role in society and how my own beliefs, attitudes and values can affect this role and its perception as a profession in society. As discussed earlier on, a teacher’s role in society is to help learners develop skills or knowledge and grow. This can be seen as both a significant and valuable contribution to the societies we live in. Therefore, teachers often serve as role models for their students, someone they look up to for compassion, passion, drive, motivation and competence. I realised that becoming a successful teacher involves continuous improvement and self-analysis to regularly re-examine these personally held beliefs and attitudes. Therefore, critical reflection and lifelong learning become vital components of any teacher’s professional career. Moreover, I was now beginning to see my role as a source of guidance and enlightenment to my pupils, something that could perhaps even make the role more valuable and challenging. I realised that being able to facilitate the students’ own learning is so much more helpful and motivating for the students than an authoritarian lecturer in most settings within HE. This is not to say that there is absolutely no place for the authoritarian teaching style. There may still be times when the subject matter, environment or an individual’s learning needs mean that a much more didactic approach is more suitable. However, being able to draw upon a range of teaching styles that complement the setting would make me a much more effective teacher. It dawned on me that those were the most impressionable years of the students’ lives and that I was supposed to be facilitating their journey of learning and skills building rather than making it more complex and challenging. I soon understood the benefits of teacher-student interactions and how students grow within classrooms that foster engagement and intellectual stimulation.

Making the Change

Re-framing

With this new understanding of the real essence of facilitative learning, the course of my professional status and autonomy changed. It was clearly time for me to address my beliefs or attitudes and seek to learn new ways to engage learners in the HE setting. I was also now understanding the power of teacher autonomy and how that works in different learning settings, such as military educational institutions. This realisation re-framed my identity as a teacher and helped me reshape my actions, thus exercising this independence of decision-making in a wholly new light. While on one hand my previous status and expertise seemed restricted and somewhat fruitless, this new understanding of the role helped me assume many new educational tasks around the institution where I could build other personal and professional skills at the same time. This proved to be a huge value-added measure for my students as they could experience a complete change in my behaviour, something that in turn brought them back to the classrooms in a happy and fun manner. Adopting the role of a facilitator would also help me to see the greater abilities in my students and challenge them not only to contribute to lesson content within their subjects but also to teach them in a highly interactive classroom environment. This deconstruction of my previously held beliefs and a new understanding of the role of a teacher in society led to me reviewing and revising my meaning perspective and meaning schemes:

Transformed meaning perspective:

Lecturing using an authoritarian approach can impede student growth and limit learning motivation.

Transformed meaning schemes:

• I cannot always impart knowledge and assume it is received in the same manner as intended

• Lecturing cannot succeed unless students are allowed to engage with one another and equally participate in all learning activities

• Power cannot be exercised over students; real power manifests in greater student engagement with the teacher and concerted involvement in learning activities

The Transformation Journey

As discussed in earlier sections, I used Mezirow’s transformative learning theory in an attempt to engage in a learning process and improve my sense of worldly impressions by journeying through the ten distinctive phases of transformation as prescribed by Mezirow:

Phase 1- A disorienting dilemma: this was the first stage of my transformation where I figured out the experience that led me towards the ultimate deconstruction of my beliefs, thus, taking me to new learning and new understandings.

Phase 2- A self-examination with feelings of guilt and shame: After receiving the feedback from my class, I experienced feelings of guilt and shame because this feedback provided me with an opportunity to see within and evaluate my behaviours and actions.

Phase 3- A critical assessment of epistemic, sociocultural, or psychic assumptions: This was a step when I evaluated how my attitude in the classroom also affected my life activities and personal behaviours. This was a realisation that this attitude has not only come from the professional role-based influences across my organisation but was actually, a total of a number of components that shaped my personality including sociocultural factors such as influences from my friends, family and peers.

Phase 4- Recognition that one’s discontent and the process of transformation are shared and that others have negotiated a similar change: I soon realised that personal transformation and discontent were joint motivators for changing my attitude, and inculcating newer beliefs based on the experienced dilemma. This led me towards a concerted approach in which change was inevitable and much more likely than at any time in the past. This was not just because I had realised that change is the only solution through which my actions will be transformed, but also because my entire personality and value systems demanded a change too.

Phase 5- Exploration of options for new roles, relationships, and actions: When I engaged in a process of self-evaluation and critical reflection, new relationships, new actions and new roles came under my investigation. I began revising the impression I had in my mind regarding the teacher-student relationship and how this could be fostered using a facilitative learning model rather than a purely authoritarian style.

Phase 6- Planning a course of action: I developed transformed meanings of the scheme and came up with three options that I deemed could be the probable solutions from this experience and critical reflection. However, only one of these three possibilities could benefit the students and cause a favourable impact on my professional career. Hence, I set out to plan alternative courses of action and figure out which one of those would best serve my motive.

Phase 7- Acquisition of knowledge and skills for implementing one’s plan: I acquired the knowledge, information and skills needed for a change of my teaching strategy during the disorientating dilemma. I read about mentoring strategies and trialled a few strategies with classes to review their outcomes and benefits in student engagement and learning practices.

Phase 8- Provisional trying of new roles: An adoption of the new role of a facilitative mentor could only mean I was onto the new path of self-recognition and re-development of self-concept and self-identity in its light. Utilising mentoring strategies such as modelling and mirroring, I was able to explore new teaching strategies and improve my practice.

Phase 9- Building competence and self-confidence in new roles and relationships. Facilitative education is all about helping students grow and providing them with the means to contribute to society in a way that suits their competencies and talents. This was also an opportunity for me to engage in a process of learning in order to re-strengthen my passion, competence, skills and confidence in the new role.

Phase 10- A reintegration into one’s life on the basis of conditions dictated by one’s perspective from an authoritarian military instructor to a facilitative teacher, the journey of self-improvement taught me how I could actually reap the benefits of my newly defined role identity (as a facilitative teacher) in my personal life too. This helped me rebuild personal relationships which had deteriorated in the initial transition period from military to civilian life.

Moving Forward

Mentoring

I had clearly identified that change was needed, and I set about discovering ways in which I could initiate this. I read a great deal about behavioural or attitude change techniques and decided that mentoring was a way in which I could explore new teaching strategies, build my confidence, and grow professionally. Mentoring is a process where an experienced person within a field shares their knowledge and guides a less experienced person, often acting as a “critical friend” whilst providing psychosocial support (Daloz, 1990). The relationship is usually an informal one in which both sides must participate and allows for positive reinforcement of effective behaviours. Strategies such as modelling and mirroring also allow mentees to witness and trial new actions or behaviours in a safe environment, based on emulating the successful behaviours and actions of the mentor (Bozeman & Feeney, 2007).

I sought out an experienced teacher within my professional field that had a successful record of academic teaching and, importantly, student satisfaction. I identified a suitable individual and they agreed to mentor me for a period of time, whilst teaching commitments were low. We agreed that I would attend some of their teaching sessions to observe and then we would meet afterwards to discuss the teaching strategies employed throughout the session. The observed sessions were extremely eye-opening for me and introduced me to a range of facilitative teaching styles that I had previously been unaware of. The informal meetings also allowed me to ask questions about the methods in an environment where I felt comfortable admitting my lack of knowledge. After a number of these sessions, I began to feel confident that I could adopt similar strategies in the classroom and one of our mentoring sessions involved me teaching a new concept to the mentor, employing my newly acquired knowledge, by way of practice. As a new academic term began, our mentoring relationship came to an end, although I do still keep in touch with the individual as the process brought us close professionally and personally.

Facilitative Teaching

After the period of self-reflection and mentoring, the first initiative I took regarding re-framing my teaching practice was to shift from an authoritarian teaching style to that of a facilitative nature. This was highly critical to promoting the development and learning of the students in my classroom. Fostering a facilitative-based learning environment requires working with the students in settings where students can take full ownership of different activities, can participate freely and do not just stick rigidly to the curriculum (Holt, Kysilka and Kysilka, 2005). They provide open-ended learning activities where students fill the gaps together while finding new ways of doing things. Hence, in such open classrooms, creativity and self-knowledge are considered norms. These students identify their experiences with the teacher’s assistance and show greater rates of engagement once they realise the benefits and efficiency of such open learning environments (Redmond, 2017).

I re-evaluated my course curriculum, broke it into a set of interactive classroom-based activities and divided the class into 5 groups comprising of 6 students each. I then administered those activities to each of these groups and facilitated their learning through encouragement and stimulation, rather than instructing them on what to do. I also consciously practised a milder tone and a softer-spoken nature within the class. In order to gain more immediate feedback, in addition to the more formal procedures, I also began to hold informal verbal sessions at the end of each teaching session. This allowed me to gauge the success of my change in practice and amend my future sessions as necessary and has become an element of each session that I now look forward to rather than dread. The resultant feedback was overwhelmingly positive and the changes I had made to my teaching practice had obviously made a striking impact on the engagement and enjoyment of the learners.

Conclusion

The findings that I have presented in this essay have undoubtedly improved my own practice as a HE practitioner and hopefully will inspire similar reflection for others around me. Of course, self-improvement is an individualistic achievement; however, the learning obtained from critical reflection on one’s activities and disorienting dilemmas can mean so much more to the wider audience. Through mentoring, I learned that others can also learn from one’s experiences and can bring positive changes to the world we all live in. An applied critique of Mezirow’s transformative learning framework provided deeper insights and reflection than I would have done normally, forcing me to question my own values and beliefs.

A stronger engagement with new knowledge construction processes allowed me a critical reflection on the existing schemes of meaning and previously held beliefs while coming across learning from newer experiences. In my case, the contextual experience I came across while teaching as an instructor within the military environment helped me interact with my knowledge base from prior experiences, revise them in the light of the feedback I received from my students, and allowed me to improve my sense of meaning of the new experience. I feel I am more open to learning now, after I have experienced what Mezirow called a “disorienting dilemma” that lead me to new knowledge avenues. Based on these reasons, I found TLT to be a beneficial and critical product of adult education scholarship.

One of the main problems I experienced with this transformative framework however lies in its deterministic emphasis on learning and transformation rather than a comprehensive theoretical discourse. Another crucial issue with Mezirow’s framework is that its framing in an interpretive paradigm overlooks the convergence and engagement between critical and positivist research paradigms that could have lent the theory, more strength and rigour. The theory also paid lesser attention towards non-Western learning styles, and thus, most of its underlying postulates remain only concerned about the “Western” idea of adult education and individual transformation. However, despite all of this, it is still concerned a very vital tenet of adult education and modern academia. I found the process both uncomfortable and enlightening but the insights I’ve gained have improved not only my professional practice but my personal relationships. Ultimately, I have found the process to be an extremely valuable tool and I intend to revisit this process regularly as I continue my transition to civilian life and journey towards becoming a highly effective, HE practitioner.

References

Ash, S. & Clayton, P. (2009) ‘Generating, deepening and documenting learning: The power of critical reflection in applied learning.’ Journal of Applied Learning in Higher Education , 1(1), pp. 25-48.

Bozeman, B. & Feeney, M. K. (2007) ‘Toward a useful theory of mentoring: A conceptual analysis and critique.’ Administration & Society . 39(6), pp. 719–739.

Brookfield, S. (2009) ‘The concept of critical reflection: Promises and contradictions.’ European Journal of Social Work , 12(3), pp.293-304.

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987) Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education. The Wingspread Journal , 9(1), pp. 1-10.

Cranton, P. (1996) Professional development as transformative learning: New perspectives for Teachers of Adults . San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Dewey, J. (1933) How We Think: A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process . Boston, MA: D.C. Heath & Co Publishers.

Daloz, L. A. (1990) Effective teaching and mentoring. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Dix, M. (2016) The cognitive spectrum of transformative learning. Journal of Transformative Education , 14(2), pp.139-162.

Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by Doing: A Guide to a Teaching And Learning Methods . Oxford Polytechnic: Further Educational Unit.

Habermas, J. (1971) Knowledge and Human lnterests . London: Heinemann.

Hess, P. (1995) Reflecting in and on practice . In Hess, P. & Mullen, E.J. (eds) Practitioner-Researcher Partnerships. Washington: NASW Press.

Holt, L.C. & Kysilka, M.L. (2005) Instructional patterns: Strategies for maximizing student learning . London: Sage.

Kabakci, I. & Şahin İzmirli, Ö. (2015) Investigation of Prospective Teachers’ Information and Communication Technology Integration Practices in Terms of Transformative Learning Theory. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice. 14(1), p. 66.

Kolb. D. A. & Fry, R. (1975) Toward an applied theory of experiential learning . In Cooper, C. (ed.) Theories of Group Proces. London: John Wiley

Kolb, D. A. (1984) Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Leon, K., Pinkert, L.A. and Taylor, K.T., (2017) ‘Developing accounts of instructor learning: Recognizing the impacts of service-learning pedagogies on writing teachers.’ Composition Studies , 45(1), p.39.

Mezirow, J. (1991) Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (1996) ‘Contemporary paradigms of learning.’ Adult Education Quarterly . 46(3), pp. 158–172.

Miettinen, R. (2000) The concept of experiential learning and John Dewey's theory of reflective thought and action. International Journal of Lifelong Education. 19(1), pp. 54-72.

Redmond, B. (2017) Reflection in Action: Developing Reflective Practice in Health and Social Services . Farnham: Ashgate.

White, S., Fook, J. & Gardner, F. (2006) Critical Reflection in Health and Social Care . New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

©David James Everiss. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence (CC BY).